Pediatric Medication Dosing Calculator

Result

Critical Measurement Comparison

Every year, 50,000 children under age 5 end up in emergency rooms because they got into medicine they weren’t supposed to. Many of these cases happen in homes parents thought were safe. A child grabs a bottle of vitamins left on the nightstand. Another swallows a single pill of their parent’s blood pressure medicine. One teaspoon instead of one milliliter. These aren’t rare mistakes-they’re common, preventable, and often deadly.

Children aren’t just small adults. Their bodies process medicine differently. Their organs are still growing. Their ability to tell you something feels wrong? Limited. That’s why pediatric medication safety isn’t just about giving less of an adult dose-it’s about rethinking everything from how you measure it to where you store it.

Why Kids Are at Higher Risk

Medication errors happen about three times more often in children than in adults. Why? Because the margin for error is razor-thin. A baby weighing 2 kilograms might need 0.5 milliliters of a medicine. A 60-kilogram teen might need 15 milliliters of the same drug. That’s a 60-fold difference in weight-and a 60-fold difference in risk.

Children’s livers and kidneys don’t work like adults’. They break down and flush out drugs slower or faster depending on their age. A dose that’s safe for a 7-year-old could overdose a 2-year-old. And because kids can’t always say, “My stomach hurts” or “I feel dizzy,” signs of trouble often go unnoticed until it’s too late.

Even something as simple as using a kitchen spoon to measure liquid medicine can be dangerous. One teaspoon equals 5 milliliters. One tablespoon equals 15 milliliters. If a parent thinks they’re giving “one teaspoon” but uses a tablespoon, that’s a threefold overdose. And if they mistake milliliters for teaspoons? Five times too much.

What Goes Wrong in Hospitals

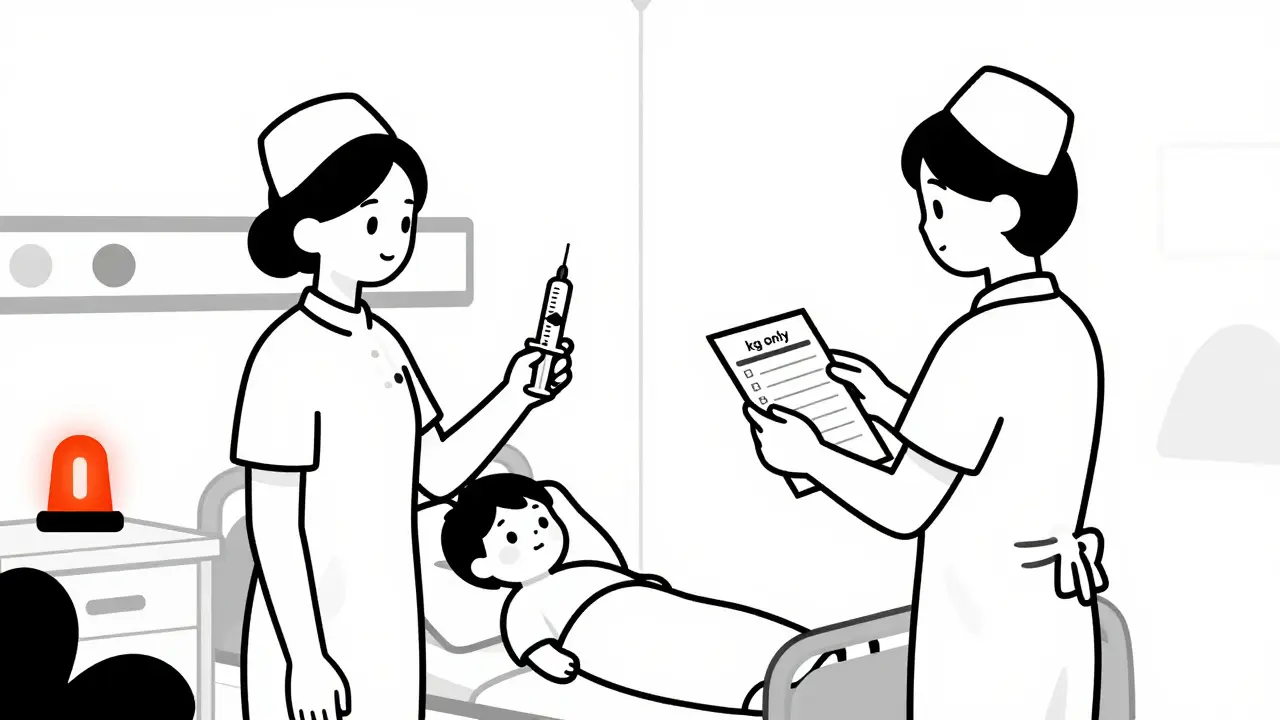

In hospitals, the biggest mistake? Weight-based dosing errors. Nearly half of all serious pediatric medication incidents are tied to getting the child’s weight wrong. Some facilities still use pounds. Others use kilograms. One wrong conversion-like thinking 20 pounds is 20 kilograms-can mean giving ten times the right dose.

That’s why leading children’s hospitals now use kilogram-only dosing. No pounds. No conversions. Just weight in kilograms, entered directly into the system. Electronic systems also have built-in limits: if a dose exceeds a safe upper threshold for a child’s weight, the system blocks it.

High-risk medications-like opioids, insulin, or heart drugs-are now given using a two-provider check. One nurse prepares it. Another double-checks the dose, the weight, the route, and the time. No shortcuts. No assumptions. This simple step cuts errors by more than half in places that use it.

Another key fix? Distraction-free zones. Medication prep areas are now kept quiet, organized, and free from phone calls or interruptions. Studies show that when nurses are rushed or interrupted, error rates jump. In pediatric units, that’s not just risky-it’s life-threatening.

Home Safety: The Real Danger Zone

Most pediatric poisonings don’t happen in hospitals. They happen at home. And parents often think they’re doing everything right.

Here’s the truth: 75% of cases involve medicine stored in places parents thought were “safe”-on a counter, in a drawer, in a purse. Children can open bottles in under 30 seconds if the cap isn’t fully locked. Even “child-resistant” caps fail if they’re not screwed on tightly every single time.

And it’s not just pills. Diaper rash cream. Eye drops. Prenatal vitamins. These are all medicines in a child’s eyes-and they can be deadly in tiny amounts. One study found that 20% of poisonings came from non-prescription products parents didn’t even think of as dangerous.

Over-the-counter cough and cold medicines? Don’t use them for kids under 6. Don’t even consider it for kids under 2. The FDA and American Academy of Pediatrics agree: they don’t work well, and the risks far outweigh any benefit.

Another big mistake? Telling kids medicine is candy. Saying “this tastes like candy” or “it’s like a lollipop” teaches them to seek out medicine. That’s how 15% of accidental ingestions happen. Kids aren’t being naughty-they’re following what they’ve been taught.

How to Measure and Give Medicine Correctly

Never use kitchen spoons. Ever.

Always use the device that comes with the medicine-a syringe, a dosing cup, or a dropper. These are marked in milliliters. That’s the only unit you should trust.

When giving liquid medicine, aim for the back of the mouth, against the cheek-not the tongue. This helps avoid choking and ensures the full dose is swallowed. If the child spits it out, don’t give more unless you’re sure they didn’t swallow any. Overdosing by trying to make up for a spit-out dose is a common error.

Use pictograms. The CDC recommends visual dosing charts-simple pictures showing how much to give at different times of day. Studies show these improve accuracy by 47%, especially for parents with low health literacy. A picture of a syringe with a line at 5 mL says more than a paragraph of text.

What You Need to Do Right Now

Here’s a simple checklist for every home with kids:

- Store all medicine-prescription, OTC, vitamins, creams-in a locked cabinet, up high, and out of sight.

- Always snap child-resistant caps shut until you hear a click. Test them: try opening them yourself. If it’s easy, they’re not closed right.

- Use only the dosing tool that came with the medicine. No spoons. No cups.

- Write down the dose, time, and reason for each medicine. Keep a list on the fridge.

- Never say medicine is candy. Say: “This is medicine. It helps you feel better, but it can hurt you if you take too much.”

- Program 800-222-1222 (Poison Help) into every phone in your house and on your cell.

What Healthcare Providers Need to Change

Hospitals that treat mostly adults often overlook pediatric safety. A 2019 study found that facilities with fewer than 100 pediatric patients per year have over three times the error rate of children’s hospitals.

Why? Because staff don’t get regular training. They don’t see kids often. They don’t know the rules.

The fix? Mandatory pediatric medication safety training for every nurse, pharmacist, and doctor-even those who rarely see kids. Competency checks should be required every year. Hospitals should use standardized concentrations for high-risk drugs. No more 10 mg/mL, 20 mg/mL, 50 mg/mL versions of the same drug. One concentration. One standard. Less room for confusion.

And when giving instructions to parents? Use the teach-back method. Don’t just hand them a sheet. Ask: “Can you show me how you’ll give this medicine tomorrow?” If they get it right, they’re more likely to remember. Studies show this cuts home errors by 35%.

What’s Next?

The FDA now requires new pediatric drugs to come in standardized concentrations. That means in the next few years, you’ll see fewer variations in liquid medicines. This alone could cut dosing errors by 60%.

More hospitals are adopting kilogram-only systems. More pharmacies are dispensing only milliliter-based dosing tools. More states are requiring pictogram instructions for home meds.

But the biggest change? Awareness. Parents need to know: medicine is not candy. A pill is not harmless. A teaspoon is not a tablespoon. And a child’s body doesn’t handle medicine the way yours does.

Every child deserves to be safe. That starts with knowing the risks-and doing something about them.

Frank Baumann

February 8, 2026 AT 20:34