Medication Driving Risk Calculator

Enter medications you've taken in the last 24 hours. Based on the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's research, this tool estimates your driving impairment risk.

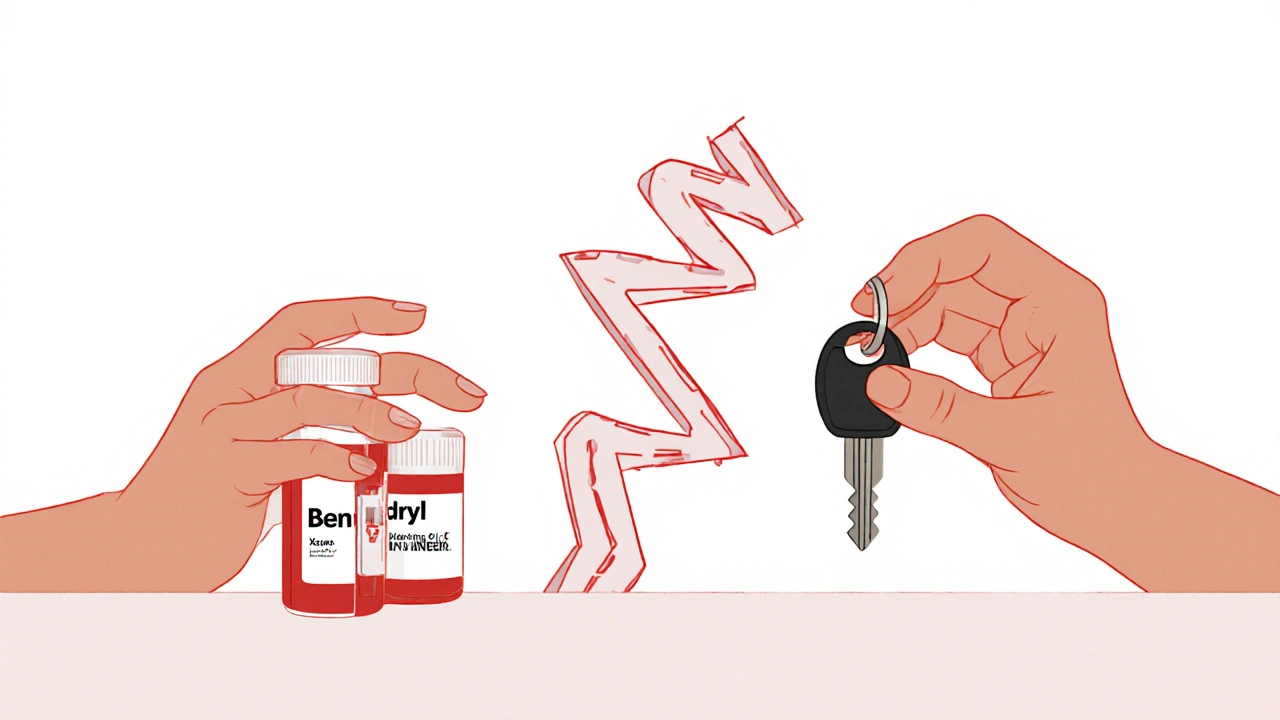

Every year, thousands of people get behind the wheel after taking a pill they think is harmless. A sleep aid. A painkiller. An allergy medicine. They feel fine. They’re not drunk. They didn’t take anything illegal. But their reaction time is slow. Their vision is blurry. Their judgment is off. And they don’t even realize it.

What Medications Actually Impair Driving?

It’s not just alcohol that makes driving dangerous. Many common medications-prescription and over-the-counter-can slow your brain, blur your vision, or make you drowsy without you noticing. The medications and driving connection isn’t theoretical. It’s backed by data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), which says drug-impaired driving causes about 18% of fatal crashes in the U.S.-second only to alcohol. Here are the top offenders:- Benzodiazepines (like Xanax, Valium): These are prescribed for anxiety and insomnia. They slow brain processing by 25-40%. Studies show they increase crash risk by 40-60%.

- Opioids (like oxycodone, fentanyl): Used for pain, they cause droopy eyelids, slowed reflexes, and reduced reaction time by up to 300 milliseconds. Crash risk goes up 25-30%.

- Antidepressants (especially tricyclics and mirtazapine): These can make you sluggish or unfocused. Research shows a 40% higher chance of being involved in a crash.

- First-generation antihistamines (like diphenhydramine in Benadryl or Tylenol PM): These are in many cold and allergy meds. They impair driving as much as a 0.10% blood alcohol level-higher than the legal limit of 0.08% in every state.

- NSAIDs (like ibuprofen, naproxen): You might think these are safe. But research shows users have a 58% higher risk of crashing.

- Sleep meds (like zolpidem/Ambien): Even if you feel awake the next morning, the drug can still be in your system. Impairment can last up to 11 hours.

Why You Don’t Realize You’re Impaired

Most people don’t feel drunk after taking these meds. That’s the problem. You take a pill at night. You sleep 8 hours. You wake up feeling fine. You drive to work. But your brain hasn’t fully cleared the drug. Your reflexes are still sluggish. Your eyes aren’t tracking properly. You think you’re okay-until you miss a stop sign or swerve into another lane. A Reddit user shared a real story: they took Tylenol PM before bed, woke up at 7 a.m., felt alert, and drove at 9 a.m. They got pulled over and failed a sobriety test. The diphenhydramine was still in their system. They didn’t know it could last that long. A 2021 AAA survey found that 63% of people didn’t know that “may cause drowsiness” on a label includes driving. Half of all drivers who take impairing meds don’t understand the risk. And only 32% of medication labels give clear timing instructions-like “don’t drive for 8 hours.”The Hidden Danger: Mixing Medications

Taking one impairing drug is risky. Taking two or more? That’s a recipe for disaster. A 2020 study found that 22% of drivers involved in trauma crashes had multiple drugs in their system-often a mix of alcohol, opioids, benzodiazepines, and antihistamines. These combinations don’t just add up; they multiply. One study showed that mixing alcohol and a benzodiazepine increased impairment by over 200% compared to either drug alone. And it’s not just illegal drugs. People think, “I’m just taking my anxiety pill and my painkiller.” But that’s exactly what makes it dangerous. The body doesn’t distinguish between “prescription” and “illicit.” It just processes the chemicals-and sometimes, the result is a brain that can’t handle the demands of driving.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Older adults are the most vulnerable group. After age 65, the body changes. It processes drugs slower. It holds onto them longer. The same dose that was safe at 50 can be dangerous at 70. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria lists over 30 medications that should be avoided in older adults because of driving risks. Yet, only 41% of doctors routinely talk to patients about driving when prescribing these drugs. Pharmacists are better-at 89%, they now warn patients about driving risks during dispensing. But that’s still not enough. Younger drivers aren’t safe either. Many take OTC sleep aids or allergy meds without thinking twice. And with more people managing multiple chronic conditions, polypharmacy (taking five or more drugs) is common. The AAA Foundation found that 70% of drivers who take three or more impairing meds still drive within two hours of taking them.Legal Consequences Are Real-and Growing

You can get a DUI for prescription drugs. In fact, all 50 states now include prescription medications in their DUI laws. But here’s the catch: unlike alcohol, there’s no universal legal limit for most drugs. Only 28 states have set specific blood concentration limits for prescription drugs. In the rest, it’s “any detectable amount” that can lead to charges. That means even if you took your medication as directed, if a blood test shows traces of it-and you were in a crash-you could be charged. Law enforcement is catching up. NHTSA’s Drug Evaluation and Classification Program is now active in 47 states. Officers are trained to spot signs of drug impairment: slow eye movement, poor balance, slurred speech. And new roadside saliva tests-launched in 2023-can detect 12 common prescription drugs with 92.7% accuracy. Fines, license suspension, jail time-it’s all possible. And your insurance? It might not cover you if you were driving under the influence of a medication, even if it was prescribed.

What You Can Do to Stay Safe

You don’t have to give up your meds. But you need to be smart about them.- Ask your doctor or pharmacist: “Could this medication affect my ability to drive?” Don’t assume it’s safe just because it’s prescribed.

- Read the label carefully. Look for words like “drowsiness,” “dizziness,” “blurred vision,” or “do not operate heavy machinery.” That includes driving.

- Wait it out. If you take a sedating drug, wait at least 6-8 hours before driving. For zolpidem, wait 12 hours. For diphenhydramine, wait 8 hours-even if you feel fine.

- Test yourself. Try a simple self-check: Can you focus on a small object for 10 seconds? Can you follow a moving target with your eyes without moving your head? If not, don’t drive.

- Never mix meds with alcohol. Ever. Even one drink can turn a mild side effect into a dangerous one.

- Use alternatives. For allergies, try second-generation antihistamines like loratadine (Claritin) or cetirizine (Zyrtec)-they’re far less impairing.

Colin Mitchell

November 14, 2025 AT 02:23