More than 350 million people worldwide are living with hepatitis B or C - and most don’t know it. These two viruses attack the liver silently, often for decades, before causing serious damage like cirrhosis or liver cancer. The good news? We now have tools to stop them in their tracks. The bad news? Too many people still aren’t getting tested or treated. Understanding how hepatitis B and C spread, how to test for them, and what’s changed in treatment isn’t just medical knowledge - it’s life-saving information.

How Hepatitis B and C Spread - And What Doesn’t Spread Them

Hepatitis B and C are both bloodborne viruses, but their transmission patterns differ in key ways. Hepatitis B is far more contagious. It can live outside the body for up to seven days on surfaces like razors, toothbrushes, or needles. You can catch it through sex, childbirth, or even sharing personal items if there’s even a tiny amount of blood involved. In places like sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, where hepatitis B is common, most infections happen in early childhood - often from mother to baby during birth.Key Transmission Routes for Hepatitis B:

- From mother to baby during delivery (accounts for 40-90% of chronic cases in high-risk regions)

- Unprotected sex with an infected partner (30-60% risk if unvaccinated)

- Sharing needles or drug equipment

- Needlestick injuries in healthcare settings (6-30% risk depending on the person’s viral load)

- Sharing razors, toothbrushes, or other items that might have blood on them

What doesn’t spread hepatitis B? Kissing, hugging, sharing food, using the same toilet, or being around someone who coughs or sneezes. It’s not airborne. It’s not casual. It’s blood and bodily fluids - and that’s it.

Hepatitis C spreads almost exclusively through blood-to-blood contact. The biggest driver today? The opioid crisis. In the U.S., two-thirds of new hepatitis C cases happen in people under 40 who inject drugs. The number of acute cases jumped 71% between 2014 and 2018. Vertical transmission - mother to baby - happens in about 5-6% of pregnancies, but it’s less common than with hepatitis B.

Who Should Be Tested - And When

Testing is the first step to stopping these viruses. The CDC now recommends everyone get tested for hepatitis C at least once in their life - no exceptions. That includes people born between 1945 and 1965, who are five times more likely to have hepatitis C than other generations. Pregnant people should be tested during every pregnancy. If you’ve ever injected drugs, even once, or gotten a tattoo in an unregulated setting, get tested.For hepatitis B, the CDC recommends universal screening for all adults at least once. But certain groups need more frequent testing:

- Healthcare workers

- People with HIV

- Men who have sex with men

- People who inject drugs

- Those with a partner or household member who has hepatitis B

- People from countries where hepatitis B is common (Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe)

- People starting cancer treatment or kidney dialysis

Testing for hepatitis B uses a panel of blood markers: HBsAg (to detect active infection), anti-HBc (to show past exposure), and anti-HBs (to confirm immunity from vaccine or past infection). Hepatitis C starts with an antibody test. If that’s positive, a follow-up HCV RNA test confirms whether the virus is still active. About 44% of people with hepatitis C don’t know they have it - that’s why universal screening matters.

Point-of-care tests are making this easier. The OraQuick HCV Rapid Antibody Test gives results in 20 minutes. New hepatitis B point-of-care tests are 98.5% accurate in field studies. These tools are changing how we reach people in prisons, homeless shelters, and rural clinics.

What’s New in Hepatitis C Treatment - And Why It’s a Game Changer

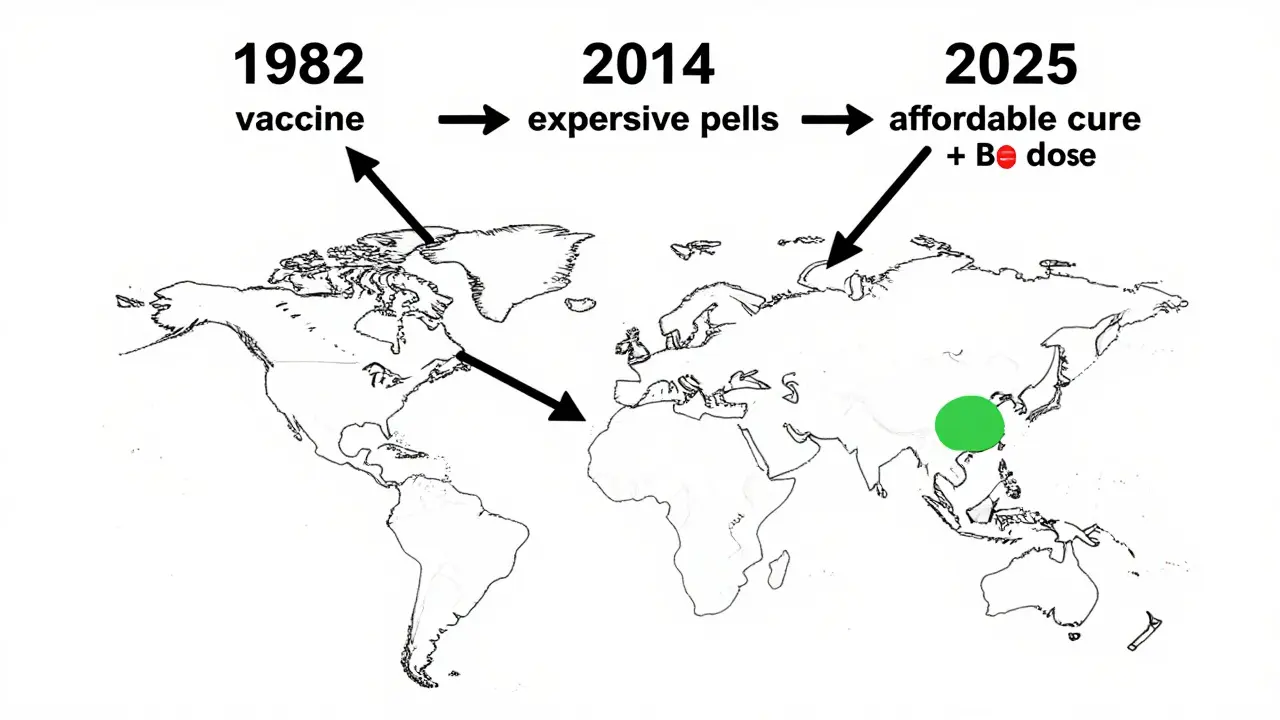

Before 2011, hepatitis C treatment meant months of painful injections, severe fatigue, depression, and a 50% cure rate. Today? It’s a simple 8-12 week course of pills. Cure rates? Over 95%. That’s not a slight improvement - it’s a revolution.Drugs like sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa) and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret) work by blocking the virus at every stage of its life cycle. They’re taken once a day, have almost no side effects, and work for all six major genotypes of hepatitis C. The treatment used to cost $84,000 per course in 2014. Now, generic versions are available for under $300 in low-income countries. In Egypt, a national campaign brought hepatitis C prevalence down from 14.7% in 2008 to 0.9% in 2021 - proof that curing this virus at scale is possible.

But access remains uneven. In the U.S., only 21% of people with hepatitis C got treated in 2020. Why? Insurance barriers, stigma, lack of providers in rural areas, and the fact that many people don’t know they’re infected. The goal now isn’t just to cure - it’s to find everyone who needs it.

Hepatitis B Treatment: No Cure Yet, But Better Control Than Ever

Unlike hepatitis C, there’s still no cure for hepatitis B. But we’ve come a long way. The goal isn’t to eliminate the virus - it’s to suppress it so the liver doesn’t get damaged. That’s where antivirals like tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) and entecavir come in. These drugs block the virus from replicating. They’re taken daily, have few side effects, and are highly effective at preventing cirrhosis and liver cancer.One big shift? Treatment is now recommended for more people. The 2025 Guidelines Update says even young adults in the "immune tolerant" phase - who used to be told to wait - should be considered for treatment if they have a family history of liver cancer, diabetes, or fatty liver disease. That’s a major change from just five years ago.

Pegylated interferon is still used in some cases, especially for younger patients hoping for a functional cure - meaning the body clears the virus on its own after treatment. About 3-7% of people achieve this after a year of interferon. It’s rare, but it happens.

And here’s the real win: when hepatitis B is well-controlled, transmission drops. Someone on effective antiviral therapy is far less likely to pass the virus to a partner or newborn. That’s why treatment isn’t just about the individual - it’s a public health tool.

The Vaccine That Changed Everything - And Why It’s Still Underused

Hepatitis B is the first cancer-preventing vaccine. Since it was approved in 1982, it’s prevented millions of liver cancer cases. The vaccine is safe, effective, and lasts at least 20 years - likely for life. It’s given in three doses, starting at birth. The World Health Organization recommends the first dose within 24 hours of birth, especially in high-risk areas.So why isn’t everyone vaccinated? In the U.S., only 66.5% of adults have completed the full series. That’s far below the 90% target. Vaccine hesitancy, lack of awareness, and fragmented healthcare systems are to blame. But the cost? It’s under $25 per dose. The vaccine is cheap. The consequences of not using it? Lifelong illness, liver transplants, and death.

Birth-dose vaccination is the most powerful tool we have to stop hepatitis B. In countries that got it right - like Taiwan - liver cancer in children dropped by 90% after introducing the birth dose. That’s the kind of impact we can replicate.

The Future: What’s Coming Next

For hepatitis C, the focus is on making treatment even simpler. WHO is testing models where nurses or community workers give the pills instead of specialists. That could bring cure rates up in places with few doctors.For hepatitis B, the holy grail is a functional cure - where the body clears HBsAg without lifelong treatment. More than 20 new drugs are in clinical trials. Some use RNA interference (siRNA) to silence the virus. Others target the virus’s core protein. Early results show promise. One drug, JNJ-3989, reduced HBsAg levels in over 80% of patients in phase 2 trials.

And there’s new hope in diagnostics. In 2023, the FDA approved the first test for HBcrAg - a biomarker that may predict who can safely stop treatment. It’s not available everywhere yet, but it’s a step toward personalized care.

Still, without action, hepatitis-related deaths could rise 24% by 2025. We have the tools. We have the science. What we’re missing is the will - to test everyone, to vaccinate every newborn, and to treat every person who needs it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you get hepatitis B from a tattoo or piercing?

Yes, if the equipment isn’t sterile. Hepatitis B can survive on surfaces for up to seven days. Always choose a licensed studio that uses single-use needles and follows strict sterilization rules. Unregulated places - like street vendors or home setups - are high-risk.

Is hepatitis C curable?

Yes. Modern direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) cure more than 95% of people with hepatitis C in just 8-12 weeks. It’s one of the most successful treatments in modern medicine. The challenge isn’t curing it - it’s finding everyone who has it.

Do I need to get tested for hepatitis B if I was vaccinated?

Most people don’t. The vaccine provides long-term protection. But if you’re a healthcare worker, have HIV, or are a sexual partner of someone with hepatitis B, your doctor may check your antibody levels (anti-HBs) to make sure you’re still protected. If levels are low, you might need a booster.

Can you have both hepatitis B and C at the same time?

Yes. About 10% of people with hepatitis C also have hepatitis B, especially if they’ve injected drugs. Treating both at the same time is possible, but it requires careful management. If you’re being treated for hepatitis C and have untreated hepatitis B, the virus can flare up after cure - so testing for both is critical.

Why is hepatitis B more common in some parts of the world?

In places like Asia and Africa, most infections happen in infancy - often from mother to child during birth. Without the birth-dose vaccine, the virus spreads easily in families and communities. Countries that started universal vaccination in the 1980s, like Taiwan and South Korea, now have less than 1% infection rates. The vaccine works - but only if it’s given.

vivek kumar

January 17, 2026 AT 11:14