TB Drug Selection Tool

Select Patient Factors

Answer these key questions to determine if Ethambutol is appropriate for your patient

Treatment Recommendation

Key Considerations

When it comes to treating pulmonary tuberculosis, Ethambutol often sits in the middle of a four‑drug cocktail, but many clinicians wonder if another pill could do the job better, cheaper, or with fewer side effects. Let’s break down how Ethambutol stacks up against its most common partners and substitutes, so you can see exactly when it shines and when another option might make more sense.

What is Ethambutol (Myambutol) and how does it work?

Ethambutol is an oral bacteriostatic agent that interferes with the synthesis of arabinogalactan, a key component of the mycobacterial cell wall. By blocking this step, the drug weakens the bacteria and helps the immune system clear the infection. In most guidelines, Ethambutol is given at 15 mg/kg daily for the intensive phase of treatment, typically the first two months.

Why Ethambutol joined the classic four‑drug regimen

The standard first‑line regimen for drug‑sensitive TB includes Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Pyrazinamide, and Ethambutol (often remembered as HRZE). Ethambutol’s role is to guard against resistance if the other drugs fail to hit the bug. It adds a different mechanism of action, reducing the chance that Mycobacterium tuberculosis will develop multi‑drug resistance.

Common alternatives to Ethambutol

When patients can’t tolerate Ethambutol-or when local resistance patterns suggest a different mix-clinicians turn to several other agents. Below is a quick snapshot of the most frequent substitutes.

- Isoniazid: A potent bactericidal drug that inhibits mycolic acid synthesis. Often the backbone of therapy, but resistance can emerge quickly if used alone.

- Rifampicin: A liver‑friendly inducer of bacterial RNA polymerase, essential for sterilizing the infection. Its strong drug‑interaction profile sometimes limits use.

- Pyrazinamide: Works best in acidic environments like those inside macrophages. It’s great for shortening therapy but can cause liver stress.

- Streptomycin: An injectable aminoglycoside that disrupts protein synthesis. Reserved for cases where oral options are unsuitable, but ototoxicity is a concern.

- Levofloxacin: A fluoroquinolone that inhibits DNA gyrase. Used increasingly for drug‑resistant TB or when patients can’t take first‑line pills.

- Bedaquiline: A newer diarylquinoline targeting ATP synthase. Primarily for multidrug‑resistant cases; it’s pricey but highly effective.

Head‑to‑head comparison

| Drug | Mechanism | Typical Dose (adult) | Main Side Effects | Cost (USD per month) | Resistance Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethambutol | Inhibits arabinogalactan synthesis | 15 mg/kg daily | Optic neuritis, peripheral neuropathy | ~$10‑15 | Low when combined with HRZ |

| Isoniazid | Blocks mycolic acid production | 5 mg/kg daily (max 300 mg) | Hepatotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy | ~$5‑10 | Moderate; high if monotherapy |

| Rifampicin | Inhibits RNA polymerase | 10 mg/kg daily | Hepatotoxicity, orange bodily fluids, drug interactions | ~$12‑20 | Low in combination, high as single agent |

| Pyrazinamide | Works in acidic pH, unknown exact target | 20-30 mg/kg daily | Hepatotoxicity, hyperuricemia | ~$8‑12 | Low when paired with HR |

| Streptomycin | Protein synthesis inhibitor (30S) | 15 mg/kg IM daily | Ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity | ~$30‑40 (injection costs) | Low if combined, high if sole agent |

| Levofloxacin | Inhibits DNA gyrase | 750 mg daily | Tendinitis, QT prolongation | ~$25‑35 | Moderate; useful in resistance |

| Bedaquiline | Blocks ATP synthase | 400 mg daily (2 weeks) then 200 mg thrice‑weekly | QT prolongation, hepatotoxicity | ~$1,200‑1,500 | Low; reserved for MDR‑TB |

When to stick with Ethambutol

If your patient has normal vision, no history of eye disease, and can tolerate daily oral meds, Ethambutol remains a solid choice. Its side‑effect profile is relatively mild compared with injectable Streptomycin or the pricey Bedaquiline. Plus, the drug is cheap and widely available in most low‑resource settings, which matters a lot for TB programs in New Zealand’s Pacific communities.

Scenarios that push you toward an alternative

There are a few red flags that make Ethambutol less attractive:

- Visual symptoms - Any colour‑vision change or blurred vision should trigger an immediate switch.

- Pregnancy - Although Ethambutol is Category C, many clinicians prefer Levofloxacin (Category B) when the fetus is at risk of optic neuritis.

- Drug‑resistant TB - When susceptibility testing shows resistance to Ethambutol, options like Bedaquiline or high‑dose Levofloxacin become front‑line.

- Severe liver disease - If the liver cannot handle Rifampicin and Pyrazinamide, a regimen leaning on Ethambutol plus a fluoroquinolone might be safer.

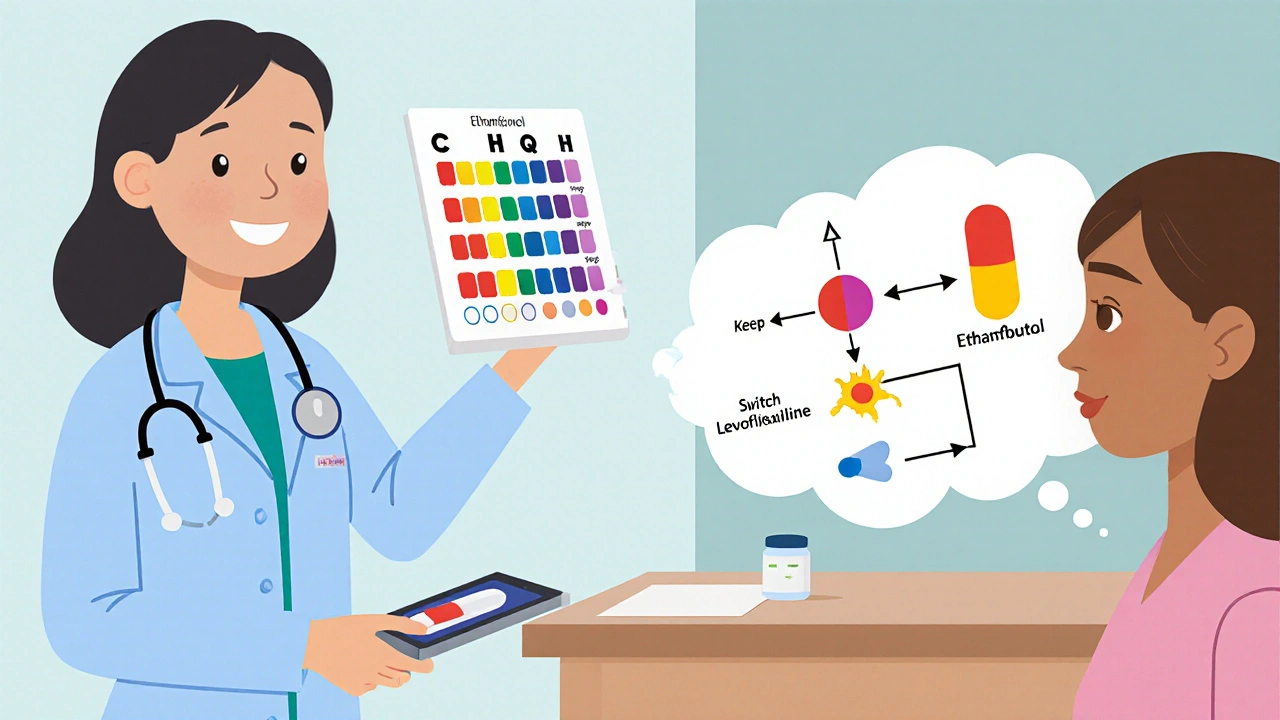

Side‑effect monitoring and management

Ethambutol’s most infamous adverse event is optic neuritis, which can lead to irreversible vision loss if not caught early. Baseline visual acuity and colour‑vision testing are a must before starting treatment, then repeat every two weeks in the intensive phase. If any deterioration appears, stop Ethambutol immediately and consider swapping in Levofloxacin.

Other drugs have their own watchlists: Isoniazid needs pyridoxine to prevent neuropathy; Rifampicin demands liver‑function testing; Pyrazinamide warrants uric‑acid monitoring. Keeping a simple checklist in the clinic helps nurses catch issues before they become serious.

Cost and accessibility considerations

In 2025, generic Ethambutol still costs under $20 per month in most countries, making it the budget‑friendly option for nationwide TB programmes. By contrast, Bedaquiline’s price hasn’t dropped much despite generic competition, staying above $1,200 per month, which limits its use to specialist centres.

Levofloxacin sits in the middle - affordable enough for private practice but still pricier than first‑line drugs. Streptomycin’s injection requirement adds logistics costs (need for cold chain, nursing time), which can be a barrier in rural areas.

Putting it all together: a quick decision guide

- Check visual baseline - if normal, Ethambutol stays.

- Review drug‑susceptibility results - resistance to Ethambutol → consider Levofloxacin or Bedaquiline.

- Assess comorbidities - liver disease favors a regimen with fewer hepatotoxic agents.

- Budget constraints - Ethambutol wins for public‑health programmes; Bedaquiline reserved for MDR‑TB.

- Patient preferences - oral daily dosing beats injectable Streptomycin for most people.

Follow these steps and you’ll land on a regimen that balances efficacy, safety, and cost.

Can Ethambutol cause permanent vision loss?

Yes, if optic neuritis isn’t caught early. Regular eye exams during the first two months usually prevent permanent damage.

Is Ethambutol safe for children?

Children can take Ethambutol, but dosing is weight‑based and eye‑monitoring is equally important.

When should I replace Ethambutol with Levofloxacin?

If the patient develops visual symptoms, has confirmed Ethambutol resistance, or is pregnant, Levofloxacin is a common swap.

How does the cost of Ethambutol compare to Bedaquiline?

Ethambutol costs under $20 per month, while Bedaquiline exceeds $1,200 - a huge difference for health‑system budgets.

Do I need to take Vitamin B6 with Ethambutol?

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) protects against neuropathy from Isoniazid, not Ethambutol. However, many TB regimens include it for overall safety.

Angela Koulouris

October 21, 2025 AT 14:51